Family Ties to Australia’s Past

History isn’t just a series of distant events—it runs through families, shaping lives in profound and personal ways. Exploring my family’s past, I’ve uncovered how deeply many of Australia’s historical controversies have impacted us. These are not just stories from textbooks; they are part of Lost Voices, Unearthed Stories—the untold tales of my ancestors and how their lives have shaped mine.

Convict Ancestry and the Legacy of Dispossession

On my maternal Mazlin side, my ancestors Hannah Brown and Thomas Marslin were convicts transported to New South Wales in the early 19th century. Like many convicts, they endured harsh conditions and strict punishments but they did survive. Eventually, their descendants settled in North Queensland, particularly in the Atherton and Mareeba areas. As my family built their lives, I can’t forget the larger context: the land they settled on was taken from its original custodians. I think about this often, balancing pride in my family’s survival with recognition of the injustice that underpinned their opportunities.

The Frontier Wars—violent conflicts between Indigenous Australians and European settlers—spanned over 140 years and resulted in widespread displacement and loss of life for Indigenous communities. This sombre backdrop underscores the complexities of Australia’s colonial history, even as I honour my ancestors’ endurance and determination. This remains a highly contested area of Australia’s past.

The Frontier Wars were a series of violent conflicts between Indigenous Australians and European settlers, spanning over 140 years, as settlers expanded across the continent, resulting in widespread displacement and loss of life for Indigenous communities.

Free Settlers

In contrast to the Mazlins, my paternal Anthonys were free settlers. Initially, the Anthonys probably left Scotland during the “Plantation of Ulster” in the early 17th Century. These settlers became known as Ulster Scots or Scots-Irish in subsequent generations. Economic challenges eventually drove them to undertake the long journey to Australia, motivated by the promise of land, freedom, and a fresh start. Settling on the Darling Downs in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Anthonys helped build the agricultural backbone of southern Queensland.

I reflect on their determination and resourcefulness, qualities that shaped future generations. The fertile Darling Downs, with its rolling plains, rich black soils, and mild climate, provided an ideal environment for farming and grazing, though the journey to success was fraught with risks and uncertainties.

The Darling Downs is a fertile agricultural region in southern Queensland characterized by rolling plains, rich black soils, and a mild climate, ideal for farming and grazing.

War and My Family

Both sides of my family have deep connections to Australia’s involvement in the world wars. Relatives fought in World War I and II; some were killed at ANZAC Cove, where so many Australians sacrificed their lives, and others served in the Middle East or closer to home. My grandfather, Victor Mazlin, was a member of the Australian Light Horse during World War I, while Maxwell Anthony fought in the Middle East during World War II.

Victor Mazlin, a member of the Australian Light Horse during World War I.

The Japanese advance through the Pacific brought the war directly to Australia’s doorstep, striking fear into the hearts of many Australians. The fall of Singapore in 1942, long considered a vital line of defence, shocked the nation, and the bombing of Darwin shortly after brought the war to Australian soil for the first time. These events marked a turning point for Australia, as the war transformed from a distant conflict to an immediate and looming threat, prompting a shift in defence strategy and greater reliance on U.S. military assistance.

In Herberton, where my family lived, the war felt much closer. The town became a rest and recreation (R&R) station for American soldiers, part of the broader Allied presence in Queensland. Its remoteness made it ideal for respite and training before troops returned to the Pacific theatre. For my mother, Vicky Mazlin, then a teenager, the passing soldiers brought glimpses of a broader world to her small Queensland town. She often chatted with them as they passed through, an experience that remained with her throughout her life. She later regaled her children with these stories, vividly describing the American soldiers as brash and larger than life—a stark contrast to the more taciturn Australians she knew and grew up with.

Maxwell Anthony fought in the Middle East During World War Two.

Post -War Immigration and Multiculturalism

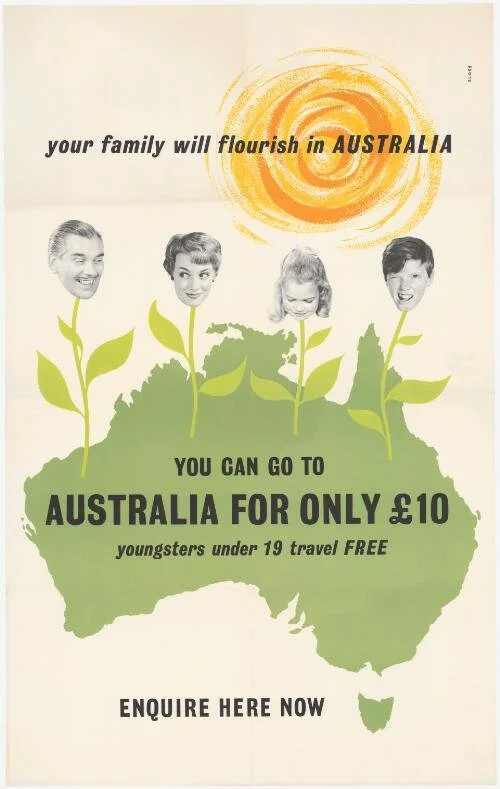

In the 1950s and 1960s, Australia was marked by post-war optimism and significant economic growth, supported by government-led immigration policies like “Populate or Perish.” These efforts brought over a million British migrants through the Ten Pound Pom scheme and attracted Southern European migrants, mainly Italians and Greeks, followed by Vietnamese refugees after the Vietnam War. These waves of migration profoundly shaped Australia’s identity, transforming it from a British colonial outpost into a multicultural society.

I recall how these communities enriched Brisbane, where I grew up. A fish and chip shop in West End served vinegar with potato chips, a nod to British traditions. Italians and Greeks kept their fruit shops open while most Australians watched cricket at the pub. Vietnamese restaurants introduced new flavours, adding to the Chinese eateries that had been around since the gold rush days. These immigrant communities made Brisbane a fascinating place for a teenager like me, and I vividly remember my first teenage crush—an immigrant student at my school whose quiet presence intrigued me and left a lasting impression.

This poster promoted an assisted passage migration scheme intended to bring British people to Australia. It featured an image of the sun, upper right, above a green map of Australia, from which four faces are growing on flower stalks.

Political Upheaval and Personal Awakening

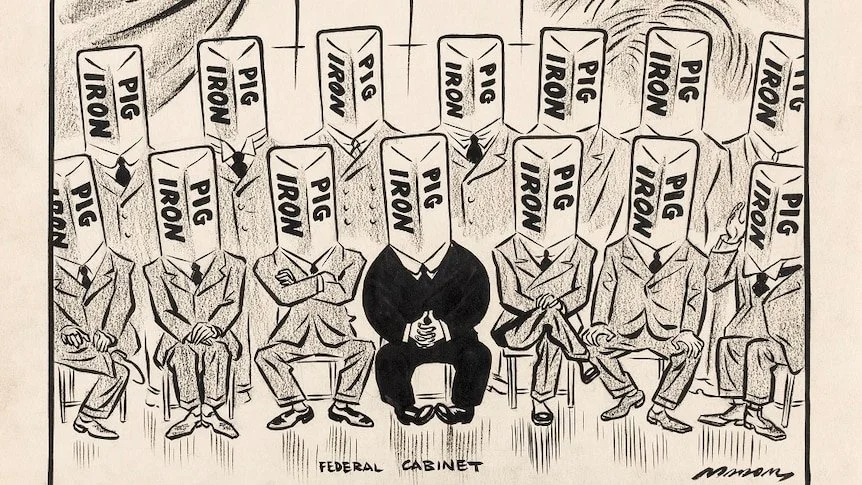

The post-war era was dominated by Robert Menzies, whose conservative policies defined Australia for nearly two decades. My mother detested Menzies and the Liberal Party in general. She would call him “Pig Iron Bob”. He earned this nickname after, as Attorney-General in 1938, he insisted on exporting pig iron to Japan despite widespread protests from Australian workers who feared the iron would be used for weapons in Japan’s militarisation efforts. Our family has always been staunch Australian Labor Party supporters.

Menzies’ Australia, from 1949 to 1966, was marked by economic prosperity, political stability, and social conservatism. Robert Menzies prioritised strong ties with Britain and the United States, promoted anti-communism, and oversaw Australia’s involvement in the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Domestically, his government championed the White Australia Policy and supported immigration from Europe, helping to build Australia’s post-war economy. While his era was one of material comfort for many Australians, it was also a time of rigid social norms and little progress on Indigenous rights or gender equality.

Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies was nicknamed Pig Iron Bob – and appeared as a fictional character in newspaper cartoons.

My Political Awakening

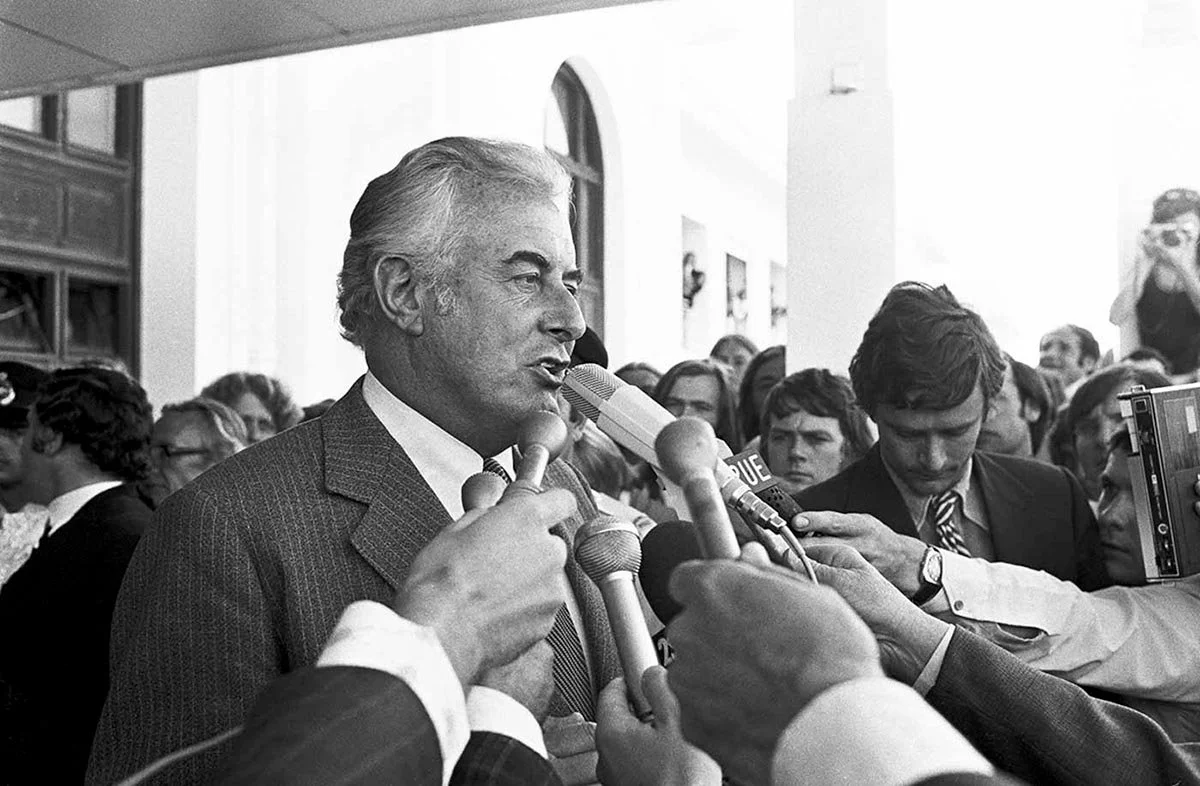

The end of the Liberal era and the election of Gough Whitlam in 1972 marked a significant shift in Australian politics. After 23 years of continuous Liberal-Country Party rule, under figures like Robert Menzies and John Gorton, Australia was ready for change. By the early 1970s, the Liberal government had grown increasingly out of touch, particularly as the country faced issues such as Vietnam War involvement, economic challenges, and growing demands for social reform. Gough Whitlam, leader of the Australian Labor Party, capitalised on this discontent with his dynamic and reform-focused It’s Time campaign, which promised sweeping health, education, and foreign policy changes. As a politically engaged student, I was captivated by Whitlam’s message of change and hope. His It’s Time campaign felt like a breath of fresh air. His victory in the 1972 election ended long-standing conservative rule. It ushered in an era of progressive reforms, including universal healthcare (Medibank), free university education, and a focus on Indigenous rights and social equity.

In 1975, Australia faced a political crisis with the Governor-General dismissing Prime Minister Gough Whitlam. That moment was shocking—it forced me to confront the fragility of democracy. I felt betrayed. That moment was pivotal in my political awakening, and it has stayed with me, becoming one of the lost voices in my personal journey that I’ve since unearthed.

The 1975 Australian constitutional crisis, also known simply as the Dismissal, culminated on 11 November 1975 with the dismissal from office of the prime minister, Gough Whitlam of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), by Sir John Kerr, the Governor-General

The Fight for Gay Rights

Of all the controversies that have shaped modern Australia, the gay rights movement and the marriage equality postal survey hold the most personal connection for me. Growing up gay in the 1970s, I was fortunate to have an accepting family and this was to have a profound impact on my life, especially given the social climate at the time when homosexuality was widely stigmatised. Their support provided me with a sense of security and belonging, shielding me from the discrimination and judgment that many in the LGBTQ+ community faced.

But Brisbane wasn’t welcoming then, and the sense of not belonging drove me to search for places where I could be myself. The unwelcoming atmosphere contributed to my decision to leave, and for years, I felt disconnected from my country. I lived in Malaysia, Thailand, China, and Japan.

When Australia overwhelmingly supported marriage equality in the 2017 postal survey, it felt like a moment of belonging and recognition—a culmination of years of struggle for rights and acceptance. For me, it was not just a legal victory but a deeply personal one — I could proudly walk down Brisbane streets holding my partner’s hand.

The 2017 Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey marked a historic moment, with a resounding 61.6% voting “Yes” in support of legalising same-sex marriage, affirming the rights of LGBTQ+ Australians to marry.

Connecting Family to History

The stories of my ancestors reflect Australia’s larger historical narratives, from convict origins and free settlement to war, migration, and social change. Through Lost Voices, Unearthed Stories, I aim to honour their strength while acknowledging the complexities of the past. What forgotten stories lie in your family’s history, and how do they connect to broader events? I encourage you to reflect and share, uncovering the events that shaped us all.

Sources

National Archives of Australia

Information on convict transportation and the early penal colonies.

Available at: National Archives of Australia

State Library of Queensland

Hstorical records about the settlement of the Darling Downs and post-war immigration waves.

Available at: State Library of Queensland

Ancestry.com

For information on your personal family history, ancestral journeys, and DNA research.

Available at: Ancestry.com

Australian War Memorial

Information on the involvement of Australians in World War I and II, particularly at ANZAC Cove and the Australian Light Horse.

Available at: Australian War Memorial

Trove (National Library of Australia)

Repositiory of ewspaper articles and cartoons from the Menzies era, including his nickname “Pig Iron Bob.”

Available at: Trove

Australian Human Rights Commission

Information on the history of the gay rights movement in Australia and the marriage equality referendum of 2017.

Available at: Australian Human Rights Commission

Hughes, Robert. The Fatal Shore: The Epic of Australia’s Founding. Vintage Books, 1987.

Kelly, Paul, and Troy Bramston. The Dismissal: In the Queen’s Name. Viking, 2015.